This program standard refers to teacher communication with families about students’ progress, which should happen on a regular basis. This also means that the teacher is respectful of others’ cultures and norms, and is available as needed for families to communicate with. Figure 1 shows a copy of a parent newsletter I have sent home as evidence of my communication with families, as a part of my family engagement plan, shown in figure 2. The engagement plan was written as a part of coursework, but I have implemented many of the strategies in it during my internship. Having an effective engagement plan for families has been shown to be incredibly important in students’ learning. A John Hopkins University evaluation found that in schools that had an effective plan, student attendance was 24% higher, and literacy achievement was improved. My family engagement plan shows reflections and notes I have made on the effectiveness of the items for family engagement. It reflects my strong interest in incorporating families into their students’ learning as much as possible, and shows my emerging competence in this area. Figure 1 shows efforts I have taken to communicate with families in a professional manner, while figure 2 demonstrates my plans for the future as well as additional items I have completed in my internship. While creating this family engagement plan, and implementing some of the items in the list, I feel that I have gained a deeper understanding of the value parents and families can bring to their child’s education, as well as their appreciation in being included. At my host school, families are very involved in their students’ education and learning, and it is easy to see how this impacts the students, both in their learning as well as their interest. By creating an effective engagement plan for my first year of teaching, I can incorporate student interests

and involve families and parents for higher understanding and engagement. In the future, I will keep my engagement plan updated so that it is relevant to my classroom, and I will write specific goals to ensure that I am acting on the items in my plan. These goals will help to keep me on track in my engagement plan as well as making my plan actionable.

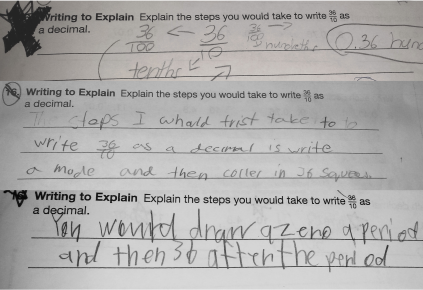

the decimal was .36, which was incorrect, and many explained how to physically write the number they came up with rather than a mathematical explanation. I was able to see several patterns while looking over these: some students had misconceptions about tenths and hundredths, some were not reading the problem carefully enough, and some were struggling with the mathematical explanation. I used this knowledge to plan my next math lesson, which helped to clarify some of these misconceptions and challenges for students. Another short assessment (in the form of a quick check) helped me to determine who understood the second lesson, and I was able to see who made progress since the first. Working with continuous informal assessments has helped me to really plan and customize the learning of my internship class, and monitor student progress.

the decimal was .36, which was incorrect, and many explained how to physically write the number they came up with rather than a mathematical explanation. I was able to see several patterns while looking over these: some students had misconceptions about tenths and hundredths, some were not reading the problem carefully enough, and some were struggling with the mathematical explanation. I used this knowledge to plan my next math lesson, which helped to clarify some of these misconceptions and challenges for students. Another short assessment (in the form of a quick check) helped me to determine who understood the second lesson, and I was able to see who made progress since the first. Working with continuous informal assessments has helped me to really plan and customize the learning of my internship class, and monitor student progress.